Gabriel René Paul was born on March 22, 1813, in St. Louis, Missouri, a city that had been founded by his maternal grandfather, the prosperous fur trader René-Auguste Chouteau, Jr. His father, Rene Paul, was a military engineer who had served as an officer in Napoleon’s army and who was wounded at Trafalgar. Paul followed in his father’s military footsteps, entering the United States Military Academy, commonly known as West Point, when he was only 16 years old. He graduated in the middle of the Class of 1834, ranked 18th of the 36 graduates.

After graduating, Paul was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 7th United States Infantry. He served in Florida in the last 1830s and early 1840s, where he participated in the Seminole Wars. Like many of the other men who would become generals during the Civil War, he served under both Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott during the Mexican-American War. He saw battle action at Fort Brown, Monterrey, Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Churubusco, Molino del Rey and Chapultepac. He was given an honorary promotion, or brevet, to the rank of major when he led a storming party and captured a Mexican army flag during the battle of Chapultepac. After the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, Paul served in several different frontier army posts and participated in several expeditions up the Rio Grande and into Utah.

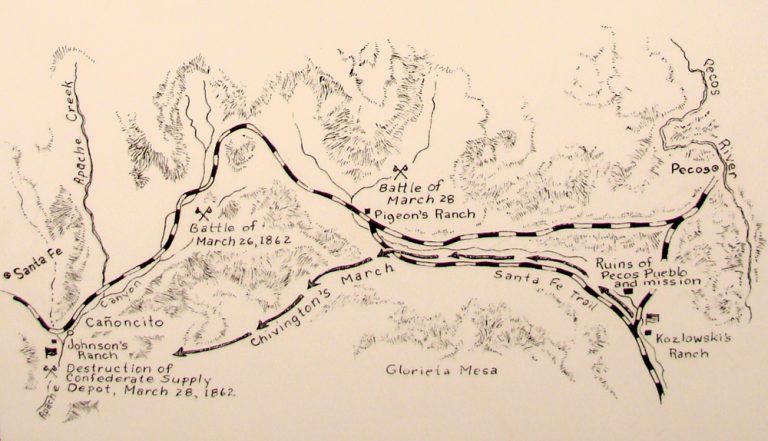

When the Civil War began, Paul was a Major in the 8th Infantry Regiment stationed at Fort Union in the New Mexico Territory. In December 1861 he was appointed Colonel of the 4th New Mexico Volunteers and commander of the fort. After the Battle of Valverde, Colonel E.R.S. Canby, the commander of all Union troops in New Mexico, sent a message to Paul telling him to hold the fort at all costs. However, when Colonel John Potts Slough arrived with his Colorado volunteers, he announced that he outranked Paul because he had been commissioned a few days earlier than Paul had. Slough deliberately ignored Canby’s orders and proceeded south with his troops, who engaged in the Battle of Glorieta, leaving Paul to guard the fort.

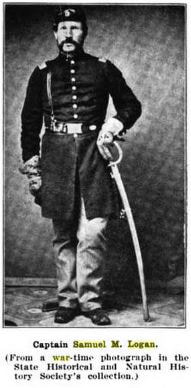

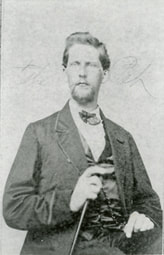

A portrait taken after Gettysburg. If you look closely, it is clear that his eye socket is empty.

A portrait taken after Gettysburg. If you look closely, it is clear that his eye socket is empty. At Gettysburg, he was transferred to a brigade in 2nd Division, where he led the soldiers of the 16th Maine, 13th Massachusetts, 94th and 104th New York, and 107th Pennsylvania Infantries as they threw up makeshift barricades and entrenchments in front of the Lutheran Seminary building during the early parts of the first day of fighting. When some 8,000 Confederates backed with 16 cannons began making significant inroads into the Union First Corps’s exposed right flank along a prominent rise of ground known as Oak Hill Ridge, the Second Corps was called in. When Henry Baxter’s brigade was nearly out of ammunition, Gabriel Paul’s brigade was brought forward to take its place. It was soon after his men had arrived on Oak Hill that he was struck in the head by a bullet that entered behind his right eye, passed through his head, and exited through his left eye socket. The men who watched him fall believed that Paul had been killed and left him where he lay as the battle intensified. Late in the afternoon, the First Corps and Eleventh Corps troops surrounding Paul’s brigade broke and began to retreat. Baxter’s and Paul’s men followed. When the division reformed on Cemetery Hill, it was discovered that 1,667 of the approximately 2,500 men who had gone into battle that morning had become casualties. Paul was one of the 776 men killed, wounded, or missing from his brigade.

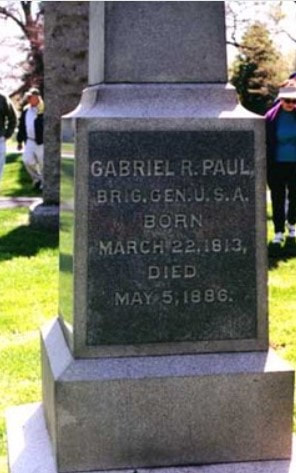

When soldiers returned to the field to search for living among the dead, they found Paul and carried him to a field hospital in the rear. Later, Paul was brevetted a Brigadier General in the Regular Army “For Gallant and Meritorious Service at the Battle of Gettysburg.” He was completely blind and his sense of smell and hearing were seriously impaired for the rest of his life, and he suffered frequent headaches and seizures, yet he refused to leave the service. He worked as Deputy Governor of the Soldier’s Home near Washington, and then was the administrator of the Military Asylum at Harrodsburg, Kentucky. On December 20, 1866, he finally retired.

The Battle of Gettysburg claimed the lives of more generals than any other battle in the American Civil War. Six general officers fell either dead or fatally wounded at both Antietam and Franklin. By most accounts, nine generals were either killed or listed among the mortally wounded at Gettysburg. The casualties include four Union (John Reynolds, Samuel Zook, Stephen Weed, Elon Farnsworth) and five Confederates (Lewis Armistead, Paul Semmes, William Barksdale, Dorsey Pender, Richard Garnett.) If we include Strong Vincent, who fell atop Little Round Top and who was posthumously honored with a promotion to brigadier general, the number climbs to ten, five for each side. I think that Gabriel Paul should be included in this list, even though he didn’t die until much later. He represents the countless many whose lives ended due to the Civil War, even if they didn’t die.